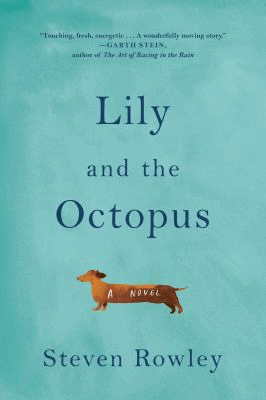

Steven Rowley’s debut novel Lily and the Octopus is about the bond between man and dog, between friends and also lovers. It follows frustrated writer and chronic first-dater Ted and his dog, best friend ever and constant companion and confidant Lily, a 12-year-old dachshund who develops a brain tumor. Yes, it’s sad, and yes, it will probably make you cry.

But before I tell you about how much I loved Lily and the Octopus, let me tell you a little bit about my own 12-year-old dog.

Lexi is a Pembroke Welsh corgi, and I’ve had her since she was five weeks old. Like Rowley’s Lily, she is long and low to the ground, and she is my best friend. We have traveled up and down the East Coast, climbed mountains and walked more miles than I can count. She has seen me through two unhappy breakups and been there for all my major accomplishments of the past decade. She knows when I am sick or feeling low, and is always quick to cheer me up by nudging me with her little nose or hrrff-ing at me until I can’t help but laugh. When I pull out her leash she trembles with anticipation and excitement. Walking is her absolute favorite thing in the universe.

The problem is that Lexi can’t walk anymore. A few months ago, she was diagnosed with degenerative myelopathy, a nerve disorder that’s similar to ALS in people. Lexi can hardly use her back legs at all. Eventually she will lose function of her front legs as well. Until her doggie wheelchair arrives, she cannot go for walks. She has always been a laid-back dog, and she’s still happy to sit outside, sniff the air and bark at passersby. But she’s not young anymore. Even with her wheelchair, she can’t climb any more mountains or go on long hikes.

So you can see how Lily and the Octopus hit me hard, right in the heart. Far from being upsetting or depressing, though, this novel is magical and amazing, and reminded me why I love Lexi so much, and why, no matter what happens with the progression of her disease, she will always be worth it.

Steven Rowley perfectly captures the bonds we form with our dogs while avoiding all the usual “man’s best friend” cliches. Lily is personified in the novel. She speaks to Ted, plays Monopoly with him, watches movies with him, talks about boys she likes with him. When she develops a brain tumor, it too, is personified as the eponymous octopus. She begins to have scary seizures and get confused. Ted engages the octopus in verbal sparring and does everything he can think of to get rid of it.

While Ted and Lily do battle with their eight-legged nemesis, Ted goes on a long string of first dates, none of which he feels great about. He feels guilty for leaving Lily alone so much, and he’s not entirely over his last long-term relationship. His writing career has stalled, and he generally feels unmoored. As Lily’s octopus grows in size and power, Ted’s life begins to unravel.

Rowley’s writing is effortless. Never once did I have to stop and re-read a sentence because it had become too tangled. Every word felt precise and sincere. Every word felt necessary and true.

The book’s ending is both expected and unexpected. It is sad, devastating even, but also spring-like in its hope.

As Lily declines and Ted ruminates on the nature of death and our foreknowledge of it, he asks:

“Or is it the promise of death that inspires life? That we must grab what we can while there is still time. Is it the not knowing if today is that day that keeps us going?

But what if this is the day? What if the hour is here?

How do you stand?

How do you breathe?

How do you go on?” (p. 256)

Those questions are never easy to answer, and the answers change depending on the person (or dog) and the situation. But Lily and the Octopus provides a good starting point.

Learn the Way Forward

Reserve a copy of Lily and the OctopusKelly reads, writes and sometimes sews, always with a large mug of tea. Her job as the Clerical Specialist at CLP – West End gives her plenty of ideas for stories that find homes in obscure literary magazines