Ever wondered how the first Census began? What has changed over time? Why they ask certain questions? Let’s dive in to some of these questions using Library resources and research.

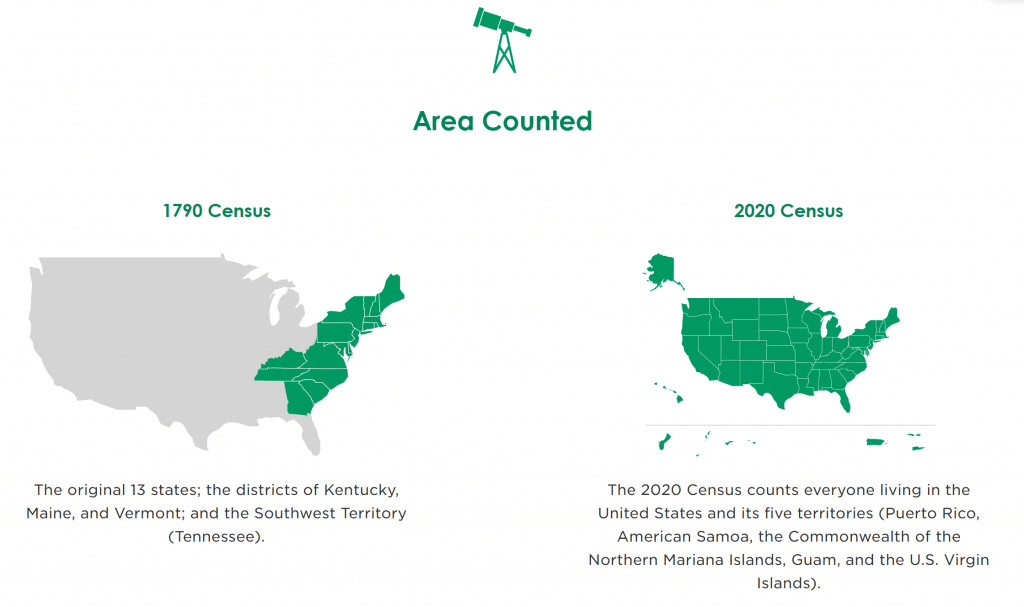

The first Census Day took place on August 2, 1790. Rather than the door-knocking (or texting) enumerators we know today, the original census takers rode on horseback to find, question and catalog the population of the United States. Check out the image below to see the difference in which areas of the country were counted in the 1790 versus 2020 Census:

The first Census began more than a year after the inauguration of President Washington and shortly before the second session of the first Congress ended. Congress assigned responsibility for the first Census to the marshals of the U.S. judicial districts under an act which, with minor modifications and extensions, governed Census taking through 1840. The law required that every household be visited, that completed Census schedules be posted in “two of the most public places within [each jurisdiction], there to remain for the inspection of all concerned…” and that “the aggregate amount of each description of persons” for every district be transmitted to the President.

According to the Population Reference Bureau: “The population of the United States today is nearly 85 times larger than it was during that first Census. The land area of the nation has changed. Technology and social structures have changed. And while the primary purpose of the Decennial Census remains the same—determining the number of seats each state occupies in the U.S. House of Representatives—uses of the data have grown.”

So why does the Census ask questions about my race/ethnicity?

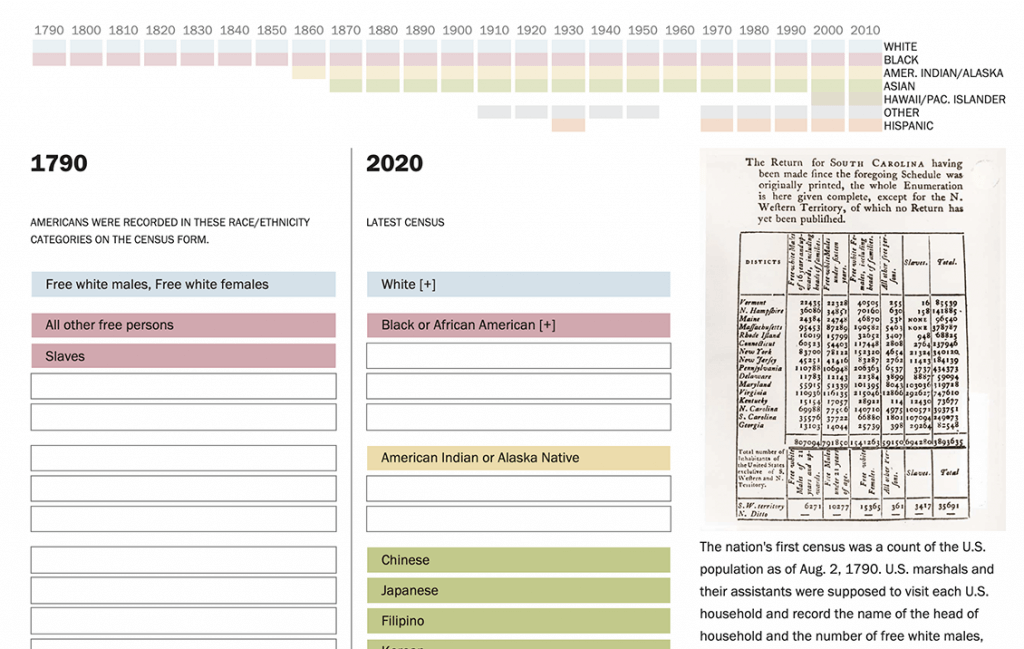

The Pew Research Center published information on the changing categories the U.S. Census has used to measure race (see image below). This timeline represents a snapshot of our changing nation, and how the way people are recorded has evolved based on the increase of immigrants/refugees into the U.S., scientific and political trends over time, as well as how society views the meaning of race and ethnicity.

Also from the Pew Research Center:

“Along with new ways to think about race have come new ways to use race data collected by the census. Race and Hispanic origin data are used in the enforcement of equal employment opportunity and other anti-discrimination laws. When state officials redraw the boundaries of congressional and other political districts, they employ census race and Hispanic origin data to comply with federal requirements that minority voting strength not be diluted. The census categories also are used by Americans as a vehicle to express personal identity.”

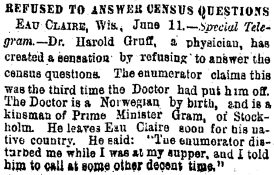

The Census has published a lot of information around the evolution of questions asked every 10 years. Most recently, they created a fact sheet about the race question. One of our Library databases, Gale Primary Sources, pulled up this newspaper story on how an enumerator in 1890 picked the wrong time to ask this doctor to take the Census:

REFUSED TO ANSWER CENSUS QUESTIONS

EAU CLAIRE, Wis., June 11. — Special Telegram. — Dr. Harold Gruff, a physician, has created a sensation by refusing to answer the census questions. The enumerator claims this was the third time the Doctor had put him off. The Doctor is a Norwegian by birth, and is a kinsman of Prime Minister Gram, of Stockholm. He leaves Eau Claire soon for his native country. He said: “The enumerator disturbed me while I was at my supper, and I told him to call at some other decent time.”

It’s important to ask questions and learn more about how the Census changes over time, and how the information collected shapes our country’s future. You can learn more by visiting the Census website, or by emailing us at info@carnegielibrary.org.

Learn More About the History of the Decennial Census

Click Here