How to Use This Guide

This is a brief introduction to the wonderful world of manga designed for educators, parents, librarians and manga enthusiasts. In this guide you will learn about the history of manga, the genres of manga, the Japanese publishing industry and about manhwa. This guide is meant to be light and informative, but not everything you need to know about manga. Manga as a form of entertainment has a rich and interesting history and it is my hope that this guide shows a glimpse into the delight that is manga.

What Is Manga?

To put it briefly, manga is the Japanese word for comics published in Japan. The word itself is comprised of two characters: man 漫 meaning “whimsical” and ga 画 meaning “pictures.”

Manga can be for entertainment or education, although in the United States manga for entertainment is what is mostly translated and published. Manga is for people of all ages and it is not seen as something just for children as compared to how sometimes American comics are viewed.

In Japan, manga is published in manga magazines such as Shōnen Jump or Shōjo Beat, multiple chapters at time, then republished into tankōbon volumes. These tankōbon volumes are what you would see in your local library or book store in the United States. Manga is printed in black and white usually because of the expense, but sometimes there are special editions that include full color chapters.

How to Properly Pronounce Manga

The correct pronunciation sounds like the “mon” in Montana plus “guh.”

How to Read Manga

Manga is read right to left beginning with the rightmost panel. The spine of the manga should be towards your right hand when you start reading, if not flip it over! Please read the panels in the following order:

Who Creates Manga?

Creators of manga are called mangaka. Mangaka are both author and illustrator of their works and each one has their own unique style of manga. Some examples of famous mangaka are Tezuka Osamu (“Astro Boy”), Akira Toriyama (“Dragon Ball Z”) and Naoko Takeuchi (“Sailor Moon”).

Brief History of Manga

Famous woodblock artist Hokusai used the term manga in the 18th century to refer to his works. Hokusai’s usage of the term referred to its literal meaning of the word, “whimsical pictures,” but his works are not the earliest examples of manga in the world. The earliest examples of what we would call manga are scrolls created by Buddhist monks in the 12th century in Japan. These scrolls ran continuously like chapters and depicted animals behaving like humans.

A manga-esque media appeared again in the 18th century with the creation of kibyōshi or “yellow covers.” Kibyōshi were books for adults that featured an illustration surrounded by dialogue and text. Many of the topics of these kibyōshi were controversial and eventually were banned by the government.

During the 19th century printing techniques became more efficient and Japanese artists continued to create comics including those that critiqued the government and discussed politics. The publishing industry continued to flourish into the 20th century, but the Japanese government began to censor artists more severely and shut down publishing houses.

Leading into WWII, manga was used by the government for the spread of Japanese imperialism and propaganda. After World War II is when modern manga began to appear and became hugely popular and successful. The American occupation of Japan brought over American style comics and this had a significant influence on the manga art style.

Beginning in 1947, artist Tezuka Osaku, who was later known as the “Father of Manga” and the “Walt Disney of Japan,” started publishing his works including the most recognizable and successful “Astro Boy.” Tezuka Osamu, along with his peers, started another monumental shift in manga from wartime propaganda to the delightful entertainment that we know and love today.

Manga Genres

Romance, slice of life, fantasy, horror, action, adventure, etc. Manga fans and librarians know these as genres, but in the manga industry things are a bit different. All of the “genres” listed above would be considered as sub-genres in the world of manga because the genres of manga are targeted demographics.

There are four main genres that you will see in manga: Shōjo, Shōnen, Josei, Seinen.

These targeted demographics are meant to be descriptive not prescriptive, meaning that although they may have a desired audience it does not meant that only members of that audience should or can read from that genre. These genres refer to specific audiences and are related to how manga is marketed in Japan. Splitting manga into these categories is a method of directly “dividing and conquering” the market along traditionally accepted gender identities and age groups. Shōnen stories feature male protagonists and tell “male” stories therefore boys buy shōnen manga. However, manga is for everyone and one should not become too focused on the names of categories because it an economic strategy not a guideline to follow.

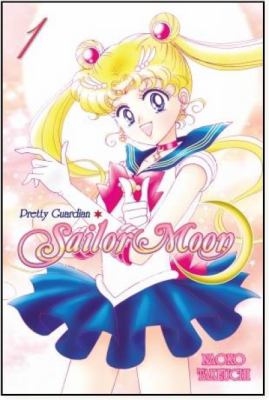

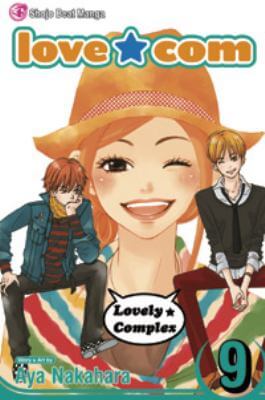

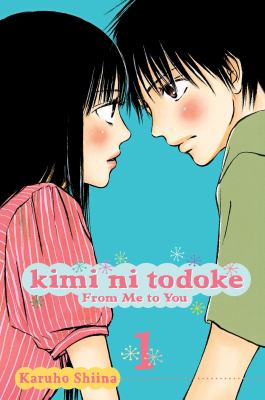

Shōjo: Shōjo means “young woman” in Japanese and the target age is under 18 years of age. Shōjo manga typically features young female protagonists. The stories in shōjo manga may be related to romance, magical girls and even comedy. Examples of shōjo include “Sailor Moon,” “Love Com,” and “Kimi ni Todoke.”

You can check out this title as a Print Book or as an eBook on Overdrive/Libby.

You can check out this title as a Print Book.

You can check out this title as a Print Book.

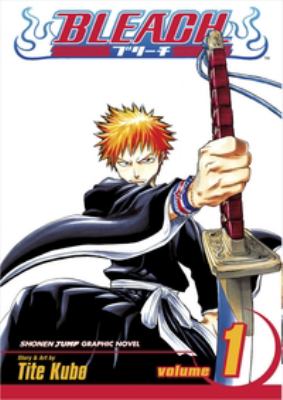

Shōnen: Shōnen means “young man” which refers to a targeted audience of boys under 18 years of age. Manga labeled under this category usually has a male protagonist and features stories of action, adventure and fantasy. Shōnen is the best selling category of manga and has many of the longest running series of all time. A few examples of these series are “One Piece,” “Bleach,” “Case Closed/Detective Conan” and “Attack on Titan.”

You can check out this title as a Print Book or as an eBook on Overdrive/Libby.

You can check out this title as a Print Book.

You can check out this title as a Print Book or as an eBook on Overdrive/Libby.

You can check out this title as a Print Book or as an eBook on Overdrive/Libby.

Josei: Josei refers to manga targeted towards women over 18 years old. Josei protagonists may be women in college or women in their 30s. Josei manga published in Japan not only has older protagonists and more mature themes and storylines, but also is written in a more complex script with more kanji and less furigana (script that is written next to kanji to aid in in reading). There is a lot of variety within this genre to appeal to an older and more mature audience, but some examples are “Princess Jellyfish,” “Tokyo Tarareba Girls,” and “Descending Stories.”

You can check out this title as a Print Book.

You can check out this title as a Print Book.

You can check out this title as a Print Book.

Seinen: Seinen refers to manga targeted towards men over the age of 18. The themes and stories found in seinen manga are more mature than those found in shōnen manga. Similar to josei manga, seinen also features more complex language including kanji that adults would know and recognize (Japanese adults are able to read and write approximately 4000 kanji while children will have learned approximately 2500 by high school). This category can be quite broad like josei, but seinen manga can share many characteristics with shōnen manga. A few examples of seinen manga are “Cowboy Bebop,” “BERSERK,” “Solanin” and “Oishinbo.”

You can check out this title as a Print Book.

You can check out this title as a Print Book.

You can check out this title as a Print Book.

You can check out this title as a Print Book.

There is often discussion about whether a manga is shōjo /josei or shōnen /seinen based on personal opinions about the maturity level and appropriateness of the content found in a manga. The genre labels are used for publishing and marketing purposes, not for censorship purposes. Whether a manga is shōnen or seinen is based on which manga magazine it was originally published in, not how mature or explicit it is. So to put it simply: proceed with caution and don’t overuse these labels. For example I have never been a teenage boy, but my favorite manga of all time is a shōnen manga and you may see me reading a josei manga series one week and seinen series the next. I personally read manga of all types as well as recommend manga of all genres to my teens regardless of their gender.

Localization and Translation

Manga is a huge part of the publishing industry in Japan, so huge that it would need its own blog post to fully discuss. In the United States, manga has to be licensed, translated and localized; a long process which can explain why your favorite manga may have currently released volume 34 in Japan, but only volume 25 in the United States. Localization, a method of altering manga to fit into the cultural norms of the targeted consumer market, is an extra step in the publication process that publishers may take depending on the manga. Examples of localization include changing the Japanese names of characters, darkening “inappropriate” scenes, swapping common Japanese snacks to more familiar American ones and censoring unseemly activity such as swearing or smoking.

Manhwa vs Manga

While browsing some cool manga online or looking up more info about manga you may have run across the term “manhwa”and wondered what it meant or if the author actually meant to write “manga.” So let’s talk about your new discovery!

Manhwa is not a typo for manga at all and is actually the Korean word for comics. Manhwa refers to comics created by Korean artists and published in Korean. The term manhwa started to be used in the 1920s during the Japanese occupation of Korea when many of Japan’s cultural elements were incorporated into Korean culture. Manhwa is read from left to right and horizontally unlike manga.

Manhwa is not printed as often as it previously was and now it is primarily created digitally and found online under the name “webtoons.”

How Do I Recommend Manga?

Sub-genres start becoming important here as well as knowing about censorship and cultural differences in Japan and the United States. As a librarian I don’t judge a book by its cover and that is especially true when it comes to manga. Sometimes manga covers are true to their content, but other times you may not know what the manga is about until you do a little research. If you are not new to manga, then you start by naming some manga you have read before. A librarian can find manga that is similar or created by the same mangaka. If you are new to manga, try to think of the type of stories you like to read. If you love romance, there is plenty manga for you, or if you are more of a sports lover there’s something for you too.

You can find new manga through publishers in the United States and you can even read a a sample of some of the chapters before they are released in the tankōbon volumes. Publishers will list all of their releases in the United States on their websites and sort them by sub-genre so you can find something perfect for you. Some popular publishers in the United States are VIZ Media, Tokyopop, Dark Horse Manga, Kodansha USA, Seven Seas Entertainment and Yen Press.

Ratings and Content

On the back cover of a volume of manga you will find a brief description, the name of the publisher and often a rating similar to those that appear on video games. Ratings that you will typically see on manga are A for all ages, T for teens, OT/T+ for older teens and M for mature. The rating system used is dependent upon publisher, but there is usually at least a rating for teens. Mild swearing and nudity are not viewed as taboo subjects in Japanese culture so these may show up in manga targeted towards tweens and teens depending on the publisher. To refer back to the discussion of manga genres, there is manga of most ratings in all four genres so do not let seinen and josei manga’s targeted audiences (adults) deter you from selecting it. As for deciding whether or not a manga is appropriate for your tween or teen, it is up to you as a caregiver.

Where to Find Manga at CLP?

At Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh, most of our manga is located in the Teen collections at the neighborhood locations, and on the First Floor and in the Teenspace at CLP – Main (Oakland).

You can also find manga online through the Library’s eResources, Hoopla and Overdrive/Libby. These items are available to borrow with your library card and read on your phone, tablet or computer!

Manga titles are always available to check out on Hoopla — there’s never a waiting list! You can link to Hoopla through our eResources page and view a Hoopla tutorial here.

You can also find manga on Overdrive/Libby, although you may have to place a hold and wait for the title to become available. You can link to Overdrive/Libby through our eResources page (or download the app onto your mobile device) and view an Overdrive/Libby tutorial here.

As always, if you are looking for a particular title or want something new, ask a librarian! You can use the Ready Reference chat box on the lower right side of your screen.

Sources

“A Beginner’s Guide to Manga” https://www.nypl.org/blog/2018/12/27/beginners-guide-manga

“The Beginnings of Anime and Manga” That Anime Project. University of Michigan Animation Group, 2001. http://umich.edu/~anime/info_animehistory.html

Diep, Edward. “A Brief History of Japanese Manga” Medium, 2019. https://medium.com/mrcomics/a-brief-history-of-japanese-manga-78dfb3a49380.

Kern, Adam L. Manga From the Floating World: Comic Book Culture and the Kibyōshi of Edo Japan. Harvard University Asia Center, 2006.

Park, InHa. “A Short History of Manhwa.” March 15, 2006. http://capcold.net/eng/blog/?p=11

Further Reading

“Osamu Tezuka was the ‘Walt Disney of Japan.’ His beautiful manga biography shows why.” https://www.vox.com/2016/8/2/12244368/osamu-tezuka-story-explained

“Manga: Heart of Pop Culture” https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2009/05/26/reference/manga-heart-of-pop-culture/#.XrT5WahKjIU

Hashimoto, Akiko. “Popular Culture: Manga.” https://www.japanpitt.pitt.edu/essays-and-articles/culture/popular-culture-manga

Ito, Kinko. “A History of Manga in the Context of Japanese Culture and Society.”