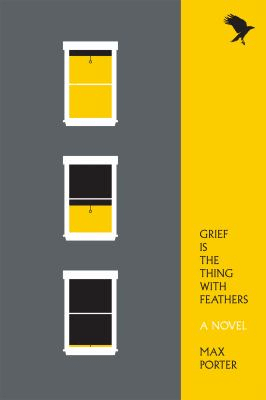

Clocking in at a mere 114 pages and titled with a clever twist on an Emily Dickinson lyric, Mark Porter’s Grief is the Thing With Feathers is a stunning summer read. You can read it as a long poem or a short novel, but it almost doesn’t matter, unless you’re a purist. It’s the lush, musical language that lifts Porter’s story out of the mundane and into the magical.

The plot is simple and sad: Mum has died unexpectedly, leaving Dad and The Boys behind. They are soon joined by Crow, a bizarre cross between a hallucination and a spirit guide, who is there to help with the grieving process. And by “help” I mean badger, pester and disturb, as crows are known to do. Dad’s latest project is a book about Ted Hughes, so Crow’s appearance isn’t exactly a surprise; in fact, it’s probably the only image that Dad could wrap his brain around at this point, faced as he is with the prospect of raising two sons on his own.

Compared to Dad and The Boys’ straightforward prose, Crow’s language is, well, shiny: full of sing-song word pairings and vivid, often disturbing, images. While battling a demon, for example, Crow describes his efforts as “whipping ligaments and nerves about joyous spaghetti tangled wool hammering, clawing, ripping, snipping, slurping, burping” (57). Dad and The Boys are, by contrast, rather blunt. Dad, for example, replaces all the chapter titles of his book with “I miss my wife,” while the Boys simply go about their business, for the most part: “We miss our Mum, we love our Dad, we wave at crows. It’s not that weird” (102). Crow seems to function as a projection of everyone’s dark emotions, acceptably processed only through an external symbol. The only exception? The language of dreams, in which both Dad and The Boys indulge from time to time. These dreams are told—as dreams often are—in the symbolic language of myth and fairy tales, another safe way for Dad and The Boys to grieve without violating the dual codes of British reserve and traditional manhood.

Instead of Kubler-Ross’s seven stages, Porter chooses a three-part structure for grief, adding an element of the Victorian novel (or possibly the theatrical) to his narrative. “Part One: A Lick of Night” introduces the characters, while “Part Two: Defence of the Nest” demonstrates how Crow’s presence both troubles the family and protects them from further harm. By the time the reader reaches “Part Three: Permission to Leave,” Crow has completed his mission, not by eliminating sorrow, but by enlarging it so Dad and The Boys can move around in it and get familiar with its geography. Crow understands his work is done before Dad and The Boys do; as he states, reasonably, “You were done being hopeless. Grieving is something you’re still doing, and something you don’t need a crow for” (103). In what is quite possibly the best elevation of the “she would want you to be happy” cliché, Dad realizes soon after Crow’s pronouncement that “if my wife’s ghost had ever haunted me, now would be the time she’d start whispering ‘You need to ask Crow to leave.'” (104).

Grief is a no-brainer pick for anyone already in the Cult of Ted (or, for that matter, Sylvia). However, this unusual novella will also appeal to anyone who has suffered a great loss, especially if expressing themselves has been difficult. Readers seeking a beach book will want to look elsewhere, but anyone hoping to dive a bit deeper into literary fiction this summer will find much to unpack here (though you might want to follow it up with something light and frothy). You’ll like Grief best, however, if you’re into wordplay and subtle humor; there’s a Coleridge reference that took me a second to get, then left me in stitches, something I didn’t expect from a poetic novella about grief, and I’ll definitely re-read this again soon, to see how many other low-key clever things I’ve missed. Finally, this book will also appeal to anyone who wants to shake up their reading routine a bit and try something new.

Ready to Take Flight?

Reserve this book in print or digital.Leigh Anne recommends good books and outwits Google daily. If you hear anybody singing or whistling in the stacks, it’s probably her.